I’m currently in a bit of a hiatus from Facebook, and, to some degree, from reading the news. The culmination of post-Brexit blues, the rise of Donald Trump, the constant barrage of news stories about people slaughtering each other with machine guns, knives and bombs around the world, the refugee crisis, the decline of the UK economy, the constant conjecture about how bleak the future is going to be, it’s all a bit much at the moment, and certainly giving me an increased feeling of Weltschmerz. Combine this with the way that I’ve seen behaviours change over the past month or so, in myself and others, where arguments have become more savage, emotions easily whipped up by unchecked facts, and accusations flung all too readily, and I feel like something is wrong, and I should step away in order to take stock. I love my friends, and I’ve always maintained that supporting others is great, but it’s rather like a human pyramid, and you’re the guy in the middle, at the bottom; if you can’t support yourself, how can you expect to support anyone else?

So I’ve switched off. Posted an apology for my absence up on Facebook for my friends, and am spending time concentrating on fixing this problem – namely, identifying what happened, why things got out of hand, and perhaps what I can do about it. Whilst doing so, I’ve take the opportunity to catch up on some of my reading list – all those sites and articles I’ve had saved, and meant to look at later. Ironically, some of the pieces I’ve found have actually given me some thoughts into not how to fix all the massive world events taking place, but rather how to approach the media on which they are being projected. Whilst this doesn’t fix everything, it might give us some insight into some of the more subtle ways in which we are affected, and what we can do, or actually have the power to fix, to improve our relationship with the outside world through them.

(NB: I appreciate that the media I’m presenting on this post is a little long. If you don’t have the time to go through it now, I do suggest that you perhaps save it, and come back later, I can heartily recommend it all, and illustrates my points more clearly.)

First up, the always fascinating Freakonomics Podcast asks “Is the internet being ruined?”:

This starts off with some interesting points – firstly the reliability on various social media platforms as a conduit for information on current events, the reasons why some are better than others, and, in turn, the reasons why those platforms are engineered that way. A lot of it comes down to the problem a lot of content producers and providers on the Internet are experiencing now, namely how do we pay to produce and provide content?

Many people believe that the Internet allows them to consume content for free. Whilst this can be true, to some extent, there are still costs incurred in creating content, and putting it up on the Internet for people to consume. Whilst there are plenty of interesting ways being dreamed up to fix this problem, from Kickstarter to Patreon, to subscription based models and even an Internet tax on your broadband costs, nothing has been found to stop people from trying to access content without paying for it.

Therefore, unsurprisingly, some platforms have gone with an advertising/sponsorship model, using the revenue gained from that to pay for the content they create, and to keep their sites running. The problem here is that the advertising has grown to such a level, that the fixation over the revenue from the advertising has overtaken the original concept of content creation and submission, that now we, the users of that platform, have stopped being the consumers, and have started to become the product. The message on the platform becomes shaped in such a way that instead of getting the information you want, you get the message they think will keep you on there the longest, and your eyeballs on the advertisers messages the longest.

(This could start, for my UX based friends out there, a massive discussion about dark patterns, data driven thinking, and the unscrupulous methods of advertising, but I’ll leave that fun for another day.)

The conclusion I feel we can bring out of this part is that we should be wary of not only the message, but also the platform on which it is being conveyed. What biases do they have, what are they trying to achieve, and where does that put us, the user, in the whole relationship? (And, maybe, are there other opportunities to get the same, or similar information, in a better relationship?)

Following on from that concept about changing our relationship with platforms such as social networks, I was shown the above video last week at work, which talks, from a designer’s perspective, about how we get distracted by many different sources, how this impacts our health, our productivity and our time, and what we could do to fix this problem. After seeing this, a colleague I was with scoffed and declared “oh, I don’t get that problem, I’ve got perfect focus!”. Whilst that may or may not be true for that person, I think this is a very real problem for the rest of us. I often find that I get quite tense when I am trying to concentrate on something, and my concentration often gets interrupted by a wealth of different sources, from the messages popping up on my screen, to the animated conversation being held by a group of developers about three metres away in my open plan office.

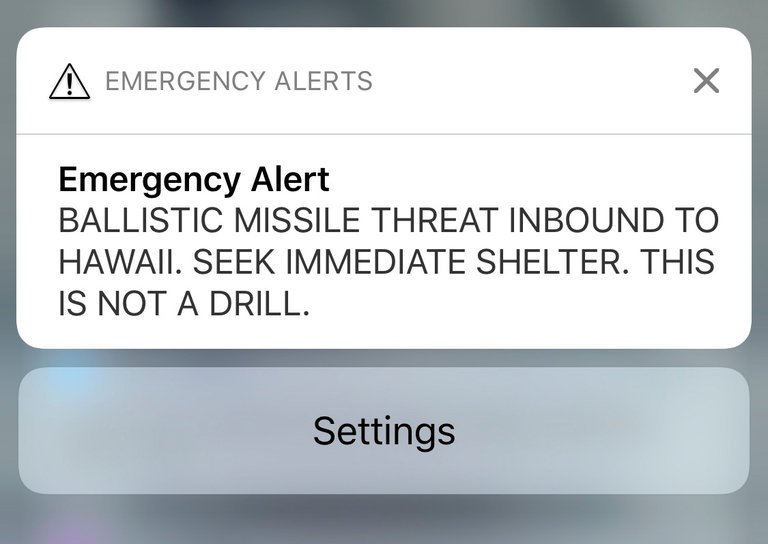

We can, in some ways, take actions to remedy these problems, turn off notifications, manage our distractions, put on some headphones to drown out the noise, and so on, but I feel that some of these problems should be solved at a more fundamental level. Taking into account the previous piece, the motives for these distractions can be troublesome, as, all of a sudden, we find that we’re being distracted so that we can contribute to advertising revenue or shareholder value, which makes me very uncomfortable. Aside from that, I firmly believe that, as a designers, my colleagues and I have a responsibility to ensure that notifications and messages put to the users should be presented in their interest, and, of course, that in any given situation, the need of the user are put first.

The final piece which has come up recently is a fascinating interview with someone who I respect greatly, Mr Stephen Fry. In this interview, he presents a viewpoint, in a way which I think is provocative to the point of being vaguely insulting to his interviewer, suggesting that his country, the United States, has in some way, failed in its attempt to become the bastion of liberty and freedom which it set out to be. Through this failure, he suggests that culture has been affected in such a way that we resort to a form of infantile behaviour, regressing to a level where we engage in childish behaviour and don’t accept anything more complex than absolutes; black and white, good and bad, and so on. Whilst I don’t fully agree with his perspective (I believe that the superhero films to which he refers have far much more scope than merely the characters hitting each other, although I will concede that, from the outside, they can look that way to a casual observer), I do agree that we have lost an appreciation of the nuances of modern life, and need to consider our approach to complex problems, and challenge ourselves wherever possible – questioning the sources of information before trusting it implicitly, and understanding the implications of the information.

So, where does this all lead us? Well, I think that the three pieces above outline some very interesting points of regarding how we relate to the world, and the conduits through which we understand it. We should, naturally, be questioning everything, and understand not only what the information we’re receiving is, but also its provenance, and the provenance of the medium on which we’re receiving it. We also need to be able to control that medium, and ensure that it’s working in such a way that it is manageable to us, and in such a way that it it works to our advantage. I certainly will be using some of these lessons to improve my relationship with the information I receive, in an attempt to not let it all get “on top of me” again. I hope you might find them useful, too.