Creating a design team in India, improving skills and permeating UX throughout a company

Introduction

This case study includes

My role

- UX Lead

Team

- Leadership

- Multifunctional product teams

- My own design team

Stakeholders

- Heads of Design

- C-suite executives

Timeline

- Various roles since 2016

Overview

Since reaching the role of UX Lead in 2016, I have both worked on creating and maturing design teams when I have been given the opportunity to do so. In other situations, I have advocated for user-centred design principles and better ways of working, both within multifunctional product teams and across wider companies. Here I share the work I’ve done, and the methods I’ve used to achieve success in my endeavours.

Building and growing a design discipline in India

I spent several years working in an international product team within a scientific publishing company, with Business and Product Management roles in Germany, and the Product Development team in India. I was then offered the chance to start a UX design team in the Pune office, as it became clear that it would be more efficient for designers to be situated in the same office as the product teams they worked with.

The brief

- To create a team of six designers who would be assigned to different product teams, understanding the specific requirements of those teams, and ensuring the designers allocated were suited to those requirements

- Providing support to my team members, helping them with their everyday work and interactions with their team and the company, and helping them to learn and mature as designers

- To work with my designers, their teams and others within the Pune office to raise awareness of user-centred design and improve working practices.

- To represent my team and advocate for their needs within the wider international design discipline, covering 36 designers in 4 countries.

Part one: recruitment

- The first stage was finding the designers to be in my team

- As I was based in London, I had to initially plan and hold the recruitment remotely, then flying across to Pune to hold in-person interviews.

- The process had various stages, mirroring the same processes that our design discipline used to recruit designers in other countries, and so not only did I have to plan interviews for myself and the candidates, but also with team members they would be working with (to ensure that they would be able to work together), as well as final interviews with the Global Head of Design.

- We found the market to be very competitive, with a limited number of candidates who had a good understanding of UX being able to pick and choose roles offered to them. As I also had limited time in which I could interview them in person, I devised a process that would after an initial screener call to assess ability, would get them into the office for a day where we could conduct interviews and practical tasks, before making them an offer by the end of the day. This method helped us to make attractive offers to candidates before another company got to them first.

- As tech roles have a strong male dominance, we wanted to ensure when advertising the role that we could appeal to as diverse a pool of candidates as possible.

- We therefore used Lou Adler’s Performance Based Hiring, a principle that advertised the role based upon what they would be doing, rather than a laundry list of skills and past achievements. This was due to the fact that candidates who weren’t male often looked at lists like these and assumed that they would not be suitable for it if they could not prove every requirements, while male candidates felt they could apply for a role if they suited some or most of the requirements.

- The HR team in our Pune office were very helpful in arranging the advertising and screening candidates, but did have some trouble adopting this new approach. I worked closely with them to help them understand these new practices, and work out the best way to review applicants.

- Thankfully, the approach worked, and we ended up hiring a very balanced and capable team.

Part two: support

- Working back in London, I would have weekly 1-2-1 sessions with each of my team members, as a chance to review the work they were doing, and discuss any questions that they were encountering. This also supplemented the fact that they could reach me at any time via Teams or email, so that questions could be answered as quickly as possible.

- I also had weekly meetings with Product Owners and Team heads to gain feedback on my team, discuss any problems, and plan initiatives to improve ways of working.

- I visited the Pune office 4-5 times a year, where I would be able to support my team in person, as well as see them working in their own teams. We would also held retrospective sessions to collect feedback from the team about their working experiences, discuss approaches and devise solutions.

- These were all then reported back to the Global Head of UX, along with my fellow UX Leads, so that we could devise a combined approach to our various teams.

Part three: development

- As the UX leadership, we defined that the two areas of focus should be:

- Improving the design skills and maturity of our teams of designers

- Improving design knowledge and practices across product teams and the wider company

- Using models generated from Jared Spool’s work, we created two tools to help us with these efforts:

1. Improving design skills

- In order to measure and improve skills across our teams in four different countries, we needed to establish a baseline on which they were all measured.

- As UX covers a wealth of different skills and disciplines, some prominent while others are less visible, we wanted to ensure that we could assess each member of our teams on those skills.

- We devised a Skills Map, detailing every skill and discipline that UX design covers, breaking them down into smaller aspects, and mapped the skills out into five areas; Research, Analysis and Strategy, Design, Delivery and Core Skills. This gave us levels of granularity to properly identify excellence and knowledge gaps.

- We then created a scale on which to measure ability in each skill, from zero (meaning that they knew absolutely nothing about this subject) through to three (meaning that they were enough of an authority on the subject that they would be willing to stand up tomorrow and give a talk about it).

- Using these scales, we were then able to sit with each of our reports and go through the Skills Map, asking them to honestly declare how comfortable they felt with each subject. Rather than just taking their word for it, we would challenge them if we felt they had under or over estimated on a certain scale.

- By doing this, we were able to draw together the final scores to understand where our reports knew a lot about a given area where we could use their knowledge to help educate others, or opportunities for improvement where we could help them understand more.

2. Improving design knowledge

- As well as assessing our designers, we wanted to run a similar process with our product teams, in order to identify opportunities for improving design knowledge and maturity, and recommend better ways of working.

- Using a UX playbook devised by Jared Spool, which defined areas of design maturity within teams and organisations, and worked on a similar 4-point scale to our Skills Maps above, we were able to conduct similar reviews with our design reports and other members of their product teams, to give their own opinions around how involved and infused UX Design was within their own working practices.

- As above, this helped us to define a UX strategy roadmap of work to help improve that design maturity within production teams and the wider company, which we could then work with our designer reports to enact.

- With this approach, we were able to get Product Owners and Business Analysts, Developers and Project Managers focussing their work around user needs. This led to better understand of not just what they were building, but the reason why they were building it, and gave them more agency and satisfaction in their work, which led them taking active interest in how the product performed after launch.

Championing better design practices

As part of the work I did in India, as well as in other roles, I’ve created and delivered programmes of work to help teams and companies realise the benefits of user-focussed production and improve their ways of working.

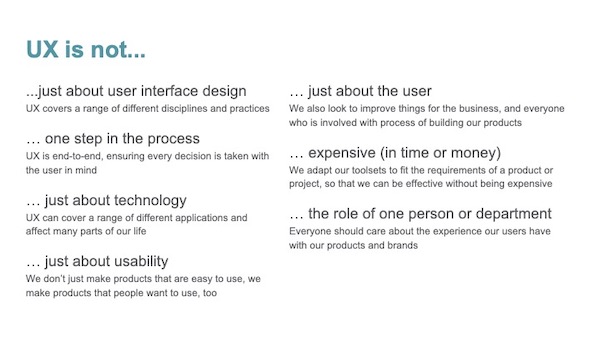

Introductory presentations

Often within companies who don’t have much design maturity, people who aren’t designers either won’t have heard of user-centred design, or will assume it’s solely the remit of the design department. In these cases, it’s often useful to start with a presentation which helps set out your position, as well as set a level between those people who have never heard of these concepts with those who might know a little.

These talks are not just standalone events, but openings to conversations and discoveries around current practices; are they confused between the terms UX and UI, do they involve users, or is the product direction solely defined by product owners, expecting the designers to just push pixels? By understanding the current situation, as with the example in India above, it helps us to create a program of work to address these understandings and improve the ways in which teams work and products are delivered. What’s more, as these things are hard to deliver alone, it helps you to identify people who might well be useful allies and advocates, to help support and spread your message.

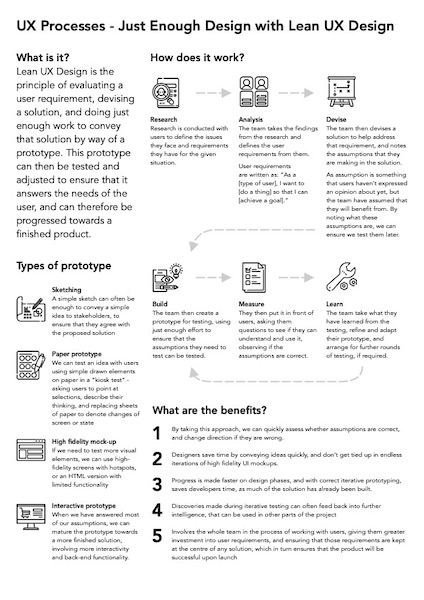

Information sheets

Whilst a presentation might be useful in informing people of your plans, it is also useful to communicate smaller concepts with colleagues and stakeholders during projects. One such method we devised was designing “One Page UX Processes”, a series of one page PDFs which we could use as a tool to help explain a concept to someone, and then leave behind with them to later review, or share with others. We designed the sheets to give a high-level overview, explaining what each concept is, how it works, and the benefits of using it.

Remote ideation workshop

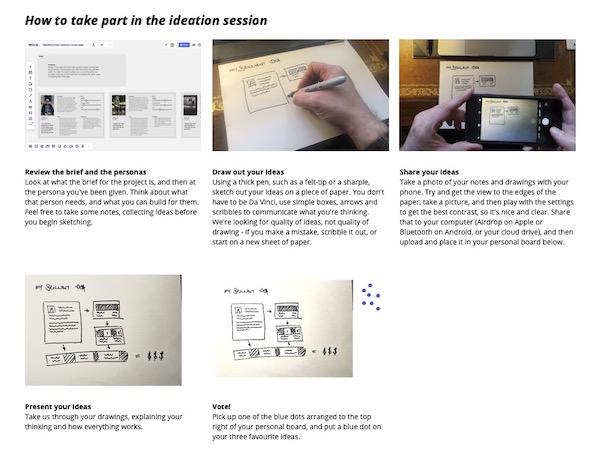

People often learn better by doing, and, when asked to provide a short workshop during a remote office activity afternoon, I saw the opportunity to provide something that would both educate and entertain. I therefore devised a small ideation workshop, which would help my colleagues to learn about the UX process, as well as having a chance to be creative, think in ways they were not used to thinking, and even introduce a note of competition around the solutions they created.

I worked out a simple open ended problem, asking them to devise a route-finding application, and then created three personas – an old man, a blind woman, and a cycle courier. I introduced the team to the problem and these three personas, and asked them to draw a solution which took the requirements of the three personas into consideration. Of course, I assured those who said that they couldn’t draw that this was conceptual, and they could communicate their ideas using boxes, arrows and wording. I gave them about 20 minutes to draw, and then asked each person to share and explain their ideas with the group, encouraging the rest of the group to ask questions and provide feedback after they had finished. The group said that they found the session highly enjoyable, and felt that they appreciated how UX design was focussed upon user needs, rather than something dreamed up by the production team.

Blog posts

UX is a continual learning process, and during my work, I also make interesting discoveries. I was invited to share some thoughts on the company blog, and so again used this as a teaching opportunity. I wanted to share details about the importance of an iterative approach to software production, but felt that just talking about that could be seen as a bit dry. I remembered the story that I had read when I was young of Percy Shaw, who discovered Cats Eyes, the road safety feature that lit up the centre white line of the road by reflecting car headlights back at them. I remembered in the story about how Shaw had iterated numerous times on his design, and had even literally “road tested” his creations on a stretch of country road late at night himself, eventually gaining a contract with the Government to produce them for UK roads, after streetlights were put out to evade bombing runs in World War II. This blog post gained praise from colleagues and clients, and became a useful link to share with people who tried to cut corners when it came to testing the products they were building.

You can read my post here on the Scott Logic blog.

The most important part: conversation

All of the above initiatives can be useful ways of communicating ideas, but their efficacy is severely diminished without one important element – conversation. This could be discussions of UX processes during a project, a chat with a colleague during a coffee break, or any number of touchpoint interactions where you get the chance to discuss how you can help with a problem. The conversations help glue together other initiatives such as the ones above, and help remind people of their existence, so that when a situation arises which could benefit from these approaches, they turn to UX for help.

As previously mentioned, you can also use these opportunities to work out the people who are more receptive and excited by how these ideas can help. These people can often turn into advocates, who can help you spread the message, and, if they are senior, might even help effect change within company-wide practices.

Conclusion

- I’ve successfully created a user-focussed production culture within several companies, both in manager and non-manager roles, helping them to work together better and deliver more successful products, which have in turn led to increased profits and happier teams.

- People in teams I have managed have gone on to excel in their careers, with the help of my mentoring. Some have risen to more senior roles afterwards, including Heads and Directors of Design.

- If you’re interested in what I could do for your company, why not get in touch?